Preparation

There's a saying "if you fail to prepare, you prepare

to fail". You've probably heard it off your instructor when you questioned

why you had to work out the wind correction to the exact degree when you

know well that winds aloft reports are usually not very accurate! Well, it's

a good idea to get prepared if you are licensed with the FAA but want to

take a flying trip in England. Here's what I found useful to do - basically

read the regulations (it's called the Air Navigation Order), get a map of

the area you'll be flying in: decide which type you want because you can

either get a quarter-millionth (same scale as a U.S. TAC - 1:250,000), or

a half-millionth (equivalent to a sectional, scale 1:500,000). Or even get

both depending on what you want to do. A book on R/T procedures (radio work)

is a good idea too because there are some differences and some concepts that

simply don't exist in the US (for details, see the next section). And

finally...have a good talk with the instructor you get checked out with.

|

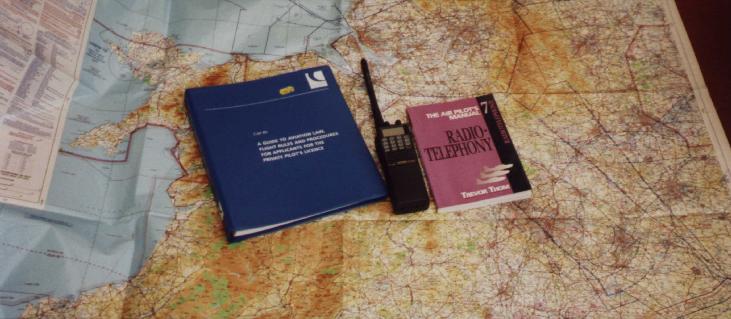

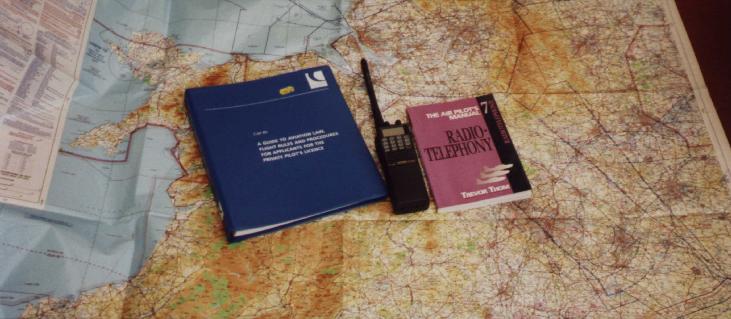

-- What to read and what you need -- |

Some useful things to have... a 1:250,000 scale map ("quarter-millionth"),

Trevor Thom's Radiotelephony book to learn radio operations, CAP 85

- A Guide to Aviation Law, Flight Rules and Procedures for Applicants for

the Private Pilot's License, and a handheld tranciever or scanner so that

you can listen to radio chatter to get used to the differences.

CAP 85 and Trevor Thom's RT book made the bulk of my reading.

CAP 85 should be supplimented by the real Air Navigation Order and reading

the AIP's etc. The ANO is FAR sized, and at Barton, the LAC had a copy of

this plus the AIP's for licensed aerodromes (a bit like the A/FD except it

covers instrument approaches and has airport diagrams) and various other

useful publications that you can peruse. Getting a copy of Pilot magazine

is good too so you can read the issues of the day (Pilot is probably the

best aviation mag I've ever read. It's really good. Additionally, Flyer has

good articles). Another thing that you had to do at Barton was read and sign

the Pilot's Order Book. This is a file with local information, noise abatement

info (such as don't fly over the graveyard to the NE of Runway 09/27 and

avoid the airport grouch's house) and safety notices from the CAA.

Study the charts, too. Most of the symbols are the same as on

a sectional, but quite a few of them are different. As an example, airports

are depicted differently. Magenta means privately owned, Blue means Government

owned (usually air force) rather than non-towered versus towered. Airspace

depiction is different too.

Prepare for a bit of a price shock. Avgas is a bit more expensive

in the UK and at the time of writing, the dollar was extremely weak relative

to the pound making it twice as expensive per hour compared to most

places in the US.

Britain is friendly towards the FAA-licensed private pilot.

You may fly G-registered aircraft day-VFR within the UK with your FAA private

pilots license. It is worth your while getting a restricted radiotelephone

license from the F.C.C. too (it lasts a lifetime and requires only minimal

paperwork).

Many GA airports in the UK are grass. Additionally, Barton is

fairly short too and the grass is not quite golf putting green standard!

However, if you apply the standard techniques you were taught as a student

about grass fields (note that grass is not necessarily a soft field!) you'll

do fine - all this talk about how flying off grass is so tough is complete

nonsense - it isn't hard at all so long as you have good airspeed control

and don't prang the nosewheel or land flat. Main wheels first isn't just

something to impress the instructor... it makes sure your nosewheel remains

attached to the airframe on a rough field! Of course you are already

used to landing a light single with the yoke all the way back, I hope!

My checkout involved the normal

PPL manouevers - some touch and goes, steep turns (to 60 degrees of bank)

and stalls. My checkout lasted an hour and held no surprises - it was pretty

much the same checkout I did when transitioning to a new aircraft in the

Bay Area Aero Club.

Get a bit of a tour of the local area from the instructor so

you can find your way home when you go solo. Around Barton, the airspace

is quite complex (Class D overlying the airport, with a SFC-1500 MSL local

flying area around Barton so you can get out of the area without having to

contact Manchester Approach, plus a low-level VFR corridor that lets you

get out to the south). The hardest thing about grass runways is finding

them! Have the instructor point out a good landmark that directs you

at the aerodrome. From 1500 ft, a grass airport looks like just another farm

field until you get close enough to see the planes parked on it.

Checklists.

Use them! The policy at LAC was use the written checklist

for ground checks (preflight, startup, run up etc) and use memorized checks

for everything in flight. For example, before stalls or steep turns, a "HASELL"

checklist is commonly used in the UK (this is good practise wherever you

are!):

H - Height Above Terrain (sufficient to recover at a safe altitude AGL)

A - Airframe, clean

S - Security: Occupants and articles

E - Engine - Temps, pressures, carb heat if required

L - Location - Clear of controlled airspace and congested areas

L - Lookout - Check clear all around and below (ie make a clearing turn)

If you use one of the locally-supplied checklists, you'll find

most of it is what you are used to with only minor differences. The instructor

I flew with was fine with things like GUMPS as a pre-landing check.

I bought one of the LAC's checklists for the Cessna 150/152/172

- they make nice flip over checklists which I think are better than what

Cessna supplies by default.

Here's what struck me particularly (apart from the fuel

price of course!) as differences you are likely to encounter:

What the hell are these Q codes!? One thing you hear

in the UK that you don't hear in the US is use of Q codes. Two of them are

very common - the rest not so common. Thom's R/T book covers them all, but

these are the ones you'll hear all the time:

QFE - Altimeter setting that will make your altimeter read zero on the

airfield.

QNH - Altimeter setting that will make your altimeter read height above mean

sea level.

You'll hear these on ATIS, from AFIS officers, from A/G outlets and from

ATC very frequently. See my section on a typical flight from Barton on how

these fit in.

I bought my chart...but it's a huge rolled up poster sized

thing! You have to fold your own charts. This may seem strange at first

but it does allow you to fold them so that things you don't want to be on

a fold in the map aren't. The best thing to do is to get it out on the floor

and decide how you are going to fold it. The charts are also laminated so

bring a supply of felt-tip pens so you can draw on them then just wipe it

off afterwards.

Flight plans: You need them if you want to fly in controlled airspace

classes A to D (most of the airspace in the UK is actually uncontrolled,

class G airspace, and in practical terms a US PPL will only ever be able

to go into Class D since class B is all above FL 240, there's no class C

and you plain aren't allowed into Class A unless you have a CAA-issued instrument

rating.) If you need to fly through class D airspace unexpectedly, you can

file over the radio. Talk to your instructor if you expect to need to do

this. For other flights, just like the FAA does, the CAA recommends that

you file a flight plan for exactly the same reasons that the FAA does.

Class A airspace: In major terminal areas like Manchester, class A

airspace gets quite close to the ground, so be careful! In London, around

Heathrow Airport there's class A to the surface!

Altimeter settings are in Millibars: The altimeter is marked this

way, so it's not a big deal. If, for some reason, you end up flying an N-numbered

plane you will need your E6B handy.

Runway lengths are metric: But don't fear, you can do the calculations

on your E6B if you want to know what it is in feet. A conservative WAG (Wild

Assed Guess) method is to just multiply meters by 3 and you'll get close

enough to feet (slightly fewer feet than reality, so it's slightly conservative).

Overhead joins: No 45 degree pattern entries. The standard circuit

entry (that's what the pattern is called in the UK) is to join overhead and

make a deadside descent. For example, at Barton, you enter the circuit at

1500 feet MSL, then make a descending turn to arrive at the 800 ft. AGL circuit

height by the time you are crosswind. You'll get to do this when you get

checked out - it's not hard and it's actually a nice procedure as you get

to observe the airport and all the traffic as you make the deadside descent

(deadside is the side of the runway not occupied by the circuit (traffic

pattern) - the "upwind" side in the U.S.). At a towered airport, you may

get instructions to join downwind or straight in depending on the circumstances

just like you would in the U.S., but you'll often get an overhead join too.

Flight levels can start as low as 3000 ft AGL (FL 030): Depending

on atmospheric pressure and the area you are flying with, you set the altimeter

to standard pressure quite low. In the UK you set the altimeter to 1013 millibars

(this is equivalent to 29.92 in Hg) when you are above the transition altitude.

Also, "flight levels" doesn't mean class A airspace as it does in the U.S.

- you can cruise up to FL240 in class G airspace in most of the country -

check the charts which clearly mark class D and class A airspace limits.

Quadrantal rule for VFR cruising altitudes: In the US, we have a

hemispheric rule. However, in the UK, cruising altitudes are defined by the

quadrantal rule once you're above the transition altitude. To summarize:

on a magnetic track of less than 090, fly at odd thousands of feet (e.g.

FL 050), 090 to 179 fly odd+500 (e.g. FL 055), 180 to 269 fly even thousands

(eg. FL 060) and 270 to 359 fly on even thousands plus 500 (e.g. FL 065).

The even and odd thousands coincide with the FAA's hemisperic rule - just

remember to fly on the thousand or thousand+500 depending on the quadrant

you're in.

Landing fees: Arrghh, you've probably read AOPA's article about user

fees. However, it hasn't quite got completely out of hand in the UK (never

saw stuff like "ramp, communication, fuel pumping fees" at Barton as is common

in Germany). However, it depends where you fly. For LAC planes, to fly back

to Barton there was no landing fee at all! Barton also has reciprocal

agreements with other airports to waive the landing fee (at the time of writing,

Barton flyers were welcome free-of-landing-fees at Ashcroft Farm, Breighton,

Crosland Moor, Netherthorpe, Mona, Sherburn-in-Elmet, Rednal, Seighford and

Sleap). Ask your instructor about this sort of thing.

Booking out: This is a procedure that's common in the UK. You have

to "book out" by filling in a few details on a booking out sheet for ATC

purposes. Booking out is done at the building marked with a big C on a yellow

background (and that's where you pay the landing fee too). At some airports

you can book out on the radio - check with the airport concerned.

The "C" is on the tower. This is where the flight school is (that's where

you book out at Barton).

ICAO signs: Although these are commonly used on large airports in

the US, they are used everywhere in the UK. The big C is just one example.

CAP 85 has pictures of them.

PPR is required wherever you go: This will probably be the biggest

culture shock - all civil airports are privately owned. This means you have

to get prior permission to use the airport to land at the airport before

you go (unless you are landing there due to unforecast weather, emergencies

etc.) The AIP contains information on who you need to phone. According to

a report I read in Pilot magazine, most RAF bases can be used by GA with

PPR, so it's not all bad. Talk to your instructor for full details.

[Back to Flying in England]

[Back to Flying]

[Home page]